Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

Our solar system used to have nine planets. Astronomer Mike Brown, also known as “the man who killed Pluto,” said he got hate mail from kids and obscene calls at 3 a.m. for years after his most famous finding helped change that.

Brown, a professor of planetary astronomy at Caltech, discovered another small world called Eris in the Kuiper Belt — a vast ring of icy objects beyond Neptune’s orbit that also happens to be the former ninth planet’s neighborhood. The 2005 revelation set off a chain of events that led to Pluto’s still-controversial demotion from planet status the following year.

But now, just as the Kuiper Belt effectively took a ninth planet away, Brown and other scientists believe it could give one back.

The belt, which astronomers believe is made of leftovers from the solar system’s formation, extends 50 times farther from the sun than Earth, with a secondary region that reaches beyond it for nearly 20 times that distance. Pluto, now classified as a dwarf planet along with Eris, is just one of the largest among the scores of icy bodies that exist there — and doesn’t dominate its own orbit and clear the orbit of other objects. That’s why it can’t have the same standing as the remaining eight planets, according to guidelines laid out by the International Astronomical Union.

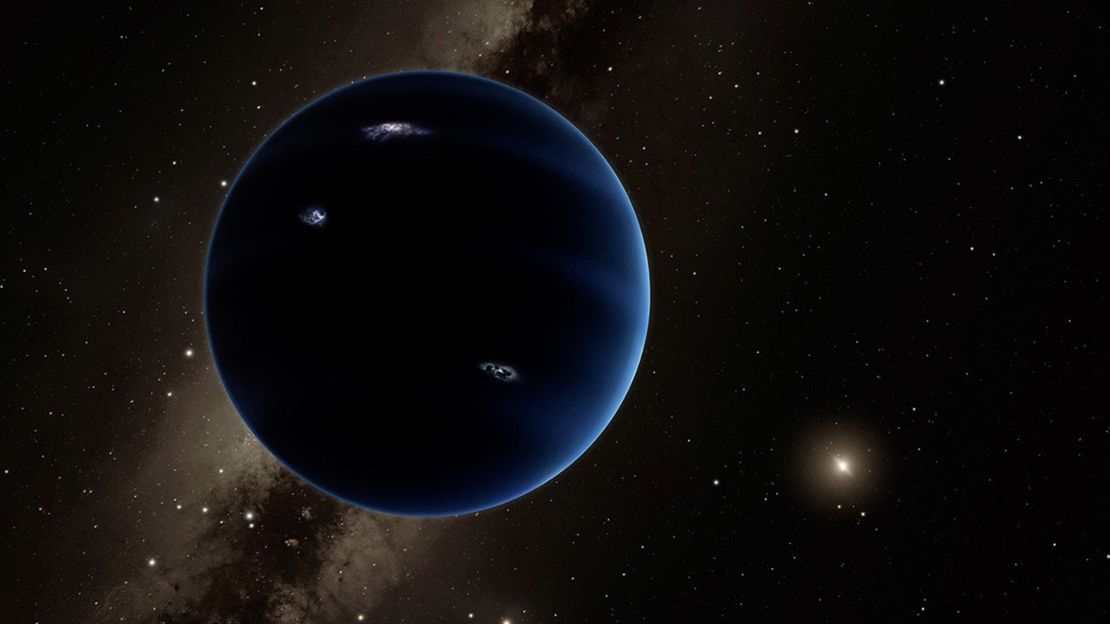

Because objects in the Kuiper Belt are so far away from the sun, however, they are difficult to spot. For more than a decade, astronomers have been searching that area for a hidden planet that has never been observed, but its presence is inferred by the behavior of other nearby objects. It’s often called Planet X or Planet Nine.

“If we find another planet, that is a really big deal,” said Malena Rice, an assistant professor of astronomy at Yale University. “It could completely reshape our understanding of the solar system and of other planetary systems, and how we fit into that context. It’s really exciting — there is a lot of potential to learn a tremendous amount about the universe.”

The excitement comes with some controversy — different camps have competing theories about the planet itself while some researchers believe it doesn’t exist at all.

“There are definitely full-blown skeptics about Planet Nine — it’s kind of a contentious topic,” Rice said. “Some people feel very passionately that it exists. Some people feel very passionately that it doesn’t. There’s a lot of debate in trying to pin down what it is, and whether it’s there. But that’s the hallmark of a really interesting topic, because otherwise people wouldn’t have heated opinions about it.”

Soon, the debate could be settled, once a new telescope capable of surveying the entire available sky every few nights comes online in late 2025. Until then, a team of researchers believes it has found the most compelling evidence yet that the hidden planet is real.

A ‘smoking gun’

The search for Planet Nine has only recently kicked into gear, but the discussion about its existence dates back more than 175 years.

“Since Neptune was successfully discovered in 1846, at least 30 astronomers have proposed the existence of various types of trans-Neptunian planets — and they’ve always been wrong,” said Konstantin Batygin, a colleague of Brown’s who is also a professor of planetary science at the California Institute of Technology. Any body orbiting the sun beyond the orbit of Neptune is defined as “trans-Neptunian” by astronomers.

“I never thought I would be talking about how there’s evidence for a trans-Neptunian planet, but I believe that unlike all of those previous times, in this case, we’re actually right,” he added.

Batygin and Brown are among the most vocal supporters of Planet Nine. The pair has been actively working on finding the hidden planet since 2014, inspired by a study by astronomers Scott Sheppard, staff scientist at the Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington, DC, and Chadwick Trujillo, associate professor of astronomy and planetary sciences at Northern Arizona University.

Sheppard and Trujillo were the first to notice that the orbits of a handful of known trans-Neptunian objects were all strangely clustered together. The duo argued that an unseen planet — several times larger than Earth and more than 200 times our planet’s distance from the sun — could be “shepherding” these smaller objects.

“The most visually striking evidence remains the earliest: that the most distant object(s) beyond Neptune all have orbits (that) point in one direction,” Brown said in an email.

Batygin has since coauthored half a dozen studies on Planet Nine, offering several lines of evidence about its existence. The strongest, he said, is in his latest work, coauthored by Brown and two other researchers and published in April in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The study tracks icy bodies subject to some kind of perturbation that’s injecting them into the orbit of Neptune before they leave the solar system entirely. “If you look at these bodies, their lifetimes are tiny compared to the age of the solar system,” Batygin said. “That means something is putting them there. And so what can it be?”

One option could be something called galactic tide, a combination of forces exerted by distant stars in the Milky Way galaxy. But Batygin and his team ran computer simulations to test this scenario versus the presence of Planet Nine, and they found that a solar system without the hidden planet is “strongly refuted by the data.”

“That’s a really remarkable smoking gun. And it’s obvious in retrospect, so I feel a little embarrassed that it took us almost a decade to figure this out. Better late than never, I suppose,” Batygin said.

Planet Nine, according to Batygin, is a “super-Earth” object, about five to seven times the mass of our planet, and its orbital period is between 10,000 and 20,000 years. “What I cannot calculate from doing simulations is where it is on its orbit, as well as its composition,” Batygin said. “The most mundane explanation is that it’s kind of a smaller version of Uranus and Neptune, and probably one of the cores that participated in the formation process of those planets.”

The super-Earth hypothesis is perhaps the one that gets the most support among Planet Nine believers, but competing theories present alternative explanations.

Super-Pluto? Competing Kuiper Belt theories

A study published in August 2023 proposes the existence of a hidden planet that’s actually much smaller, with a mass between 1.5 and 3 times that of Earth. “It’s possible that it’s an icy, rocky Earth, or a super-Pluto,” said Patryk Sofia Lykawka, an associate professor of planetary sciences at Kindai University in Japan and coauthor of the study.

“Because of its large mass, it would have a high internal energy that could sustain, for example, subsurface oceans. Its orbit would be very distant, much beyond Neptune, and much more inclined if compared to the known planets — even more inclined than Pluto’s, whose inclination is about 17 degrees,” Lykawka said. (Astronomers refer to a planet’s orbit as inclined when it’s not on the same plane as Earth’s.)

The presence of the planet is derived from computational models meant to explain the strange behaviors of populations of trans-Neptunian objects, which suggests similarities with Batygin’s research. However, Lykawka pointed out, his model does not look at the same orbital alignments and is very different from Batygin’s. That’s why he doesn’t refer to the mystery object as Planet Nine but “Kuiper Belt planet” instead, to “make it clear that we are talking about different hypothetical planets,” he explained.

Other theories propose that the anomalies everyone’s trying to explain are due to something else entirely, such as a primordial black hole — created just after the big bang — that our solar system captured as it moved across the galaxy. Another idea suggests that there might be something wrong with science’s current understanding of gravity.

But according to Rice of Yale University, these theories would be very difficult to test. “There are lots of other ideas, but I usually try to go with Occam’s razor when it comes to deciding what to prioritize in terms of checking,” she said, citing a classic principle of philosophy that states that among competing ideas, the simplest is usually correct. “In terms of scientific viability, we know that there are eight planets already, so it’s not so crazy to have another planet within the same system.”

The most promising path forward, she added, is actually finding more of the trans-Neptunian objects that Batygin is basing his hypothesis on — and proving that it’s statistically significant that their orbits are clustered.

The push for more evidence

Some researchers believe that currently scientists have detected too few of these distant trans-Neptunian objects to draw any conclusions about their orbits.

“We have about roughly a dozen or so of these objects,” said Renu Malhotra, regents professor of planetary sciences at the University of Arizona, “but we observe only the brightest ones, and only a tiny fraction of even those, because we observe them when they are at their closest approach to the sun.”

The data suffers from observational bias, according to Malhotra, which is why researchers are skeptical about it. Among the skeptics is Sheppard of the Carnegie Institution for Science, one of the coauthors of the 2014 study that inspired Batygin’s research.

“By now, we expected to have found many more of these extreme trans-Neptunian objects,” Sheppard said in an email. “Having several tens of them would allow us to reliably determine if they are truly clustered in space or not. But unfortunately we are still in the small-number statistics realm, because they are much rarer than first thought. Right now I would say it’s possible there is a super-Earth planet in the distant solar system, but we cannot say that with a lot of confidence.”

The controversy can get heated, according to Malhotra. “Scientists come in different personality types, just like everybody else. Some are more aggressive about their science, while others are more measured,” she said. “There is a perception that the idea of a Neptune-mass Planet Nine is being pushed more aggressively than the statistics justify.”

Malhotra coauthored an August 2017 paper suggesting the presence of a Mars-size planet in the Kuiper Belt, but she’s not ruling out the Planet Nine hypothesis entirely.

“It’s up in the air. It’s just at the edge of statistical significance,” she said. ”But there’s nothing in the physics we know and the observations we have that rules out the possibility of large planets at tens of times the distance of Neptune from the sun.”

Observing the planet directly would, of course, end all controversy, but every attempt so far has come up empty.

Batygin coauthored a March study that used data from the Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System, or Pan-STARRS, observatory in Hawaii, allowing researchers to analyze 78% of the sky where Planet Nine supposedly could be — but they couldn’t find it.

“It’s been a real slog,” he said about the attempt, citing the difficulty of having to work with telescopes over just a few days of allotted time while fighting against equipment breakages and adverse weather.

Spotting such a distant object without knowing where to look is exceedingly hard, and akin to searching for a target with a sniper rifle instead of binoculars, according to Batygin.

“The sky is a really, really big place when you’re looking for something so painfully dim,” he said. “This thing is something like 100 million times less bright than Neptune — that’s really pushing towards the edge of what’s possible with the absolute largest telescopes in the world right now.”

Other searches, such as one performed for a December 2021 study using the Atacama Cosmology Telescope in Chile, have also come up short. “I had to test tens of thousands of different orbits. In the end I didn’t spot anything,” said the study’s lead author Sigurd Naess, a researcher at the Institute of Theoretical Astrophysics of the University of Oslo in Norway.

The instrument’s sensitivity, he added, was good enough that it should have been able to detect a planet in an area between 300 and 600 times the distance between Earth and the sun.

“That’s enough to be informative, but far from enough to disprove Planet Nine as a whole,” Naess said in an email.

A potential ‘new chapter’

Amid controversies and diverging opinions, all of the researchers agree on one thing. A new wide-angle telescope currently under construction could soon put the debate to rest, once the US National Science Foundation and Stanford University researchers start scientific operations in late 2025. Called the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, it has the largest digital camera ever built and sits atop an 8,800-foot mountain in northern Chile.

“This is a next-generation telescope that will search the entire available sky every few days,” Batygin said. “It might just find Planet Nine directly, which would be a fantastic conclusion to the search and open up a new chapter. At the very least, it will find a ton more Kuiper Belt objects. But even if it doesn’t discover a single new object, it will be enough to confirm the Planet Nine hypothesis, because it will test all of the statistics, all of the patterns that we see with an independent survey.”

Rice agrees that the telescope will go a long way to settling the debate, and clearly address the question of the statistical significance of the alignment of trans-Neptunian objects — the key point of evidence for Planet Nine.

If the Rubin telescope finds a super-Earth, Rice said, that would be exciting because these celestial bodies, between the sizes of Earth and Neptune, are a common type of exoplanet.

“We do not have one in the solar system, which seems really strange, and has kind of been an outstanding mystery because we find so many of them in systems around other stars — it would be incredible to actually study one up close, because exoplanets are so far away that it’s very difficult to get a real grasp on exactly what they physically look like,” Rice said.

Finding a smaller planet would also spark excitement, Rice added, because every solar system planet is immensely useful for extrapolating information about the thousands of comparable exoplanets that researchers are uncovering across the galaxy.

And what if nothing shows up at all? It would still be useful to know for sure how many planets there are, Rice said. “I think not even knowing the number of planets in our own solar system is very humbling.”

That means that even the facts that many people learned from textbooks as children can change, as scientists discover more about the universe.

“That’s actually a wonderful thing,” she added. “Human knowledge is continually moving — sometimes it’s huge shifts, sometimes it’s just a back-and-forth debate. It’s a fun, emblematic example of the scientific process.”