There was a dramatic “Real Housewives” throw down on Thursday — but not a single glass of Pinot Grigio was hurled.

A New York court heard oral arguments from an attorney representing Andy Cohen, Bravo and its parent company NBC Universal, among others, about why it should toss a suit brought by former “Real Housewives” cast member Leah McSweeney.

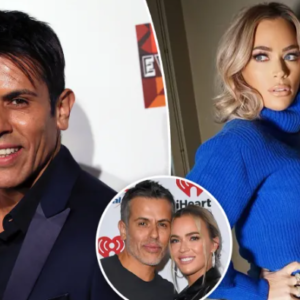

McSweeney — who is a recovering alcoholic — has claimed that the network intentionally tried to make her fall off the wagon to make more ratings-grabbing TV.

But lawyers for Cohen et al say that the court should throw out the suit because the producers’ behavior is protected by the Freedom of Speech protected by the US Constitution.

Attorney Adam Levin of Mitchell, Silberberg, Knupp argued in Manhattan Supreme Court that interactions between McSweeney and the producers — even those off-camera — were all part of their attempts to “craft a message” to the viewers, and are therefore protected by the First Amendment.

Judge Lewis J. Liman pressed Levin on whether there were limits on producers, such as whether they could “beat” a cast member off camera so long as the intention was to have them behave a certain way on camera later. He replied by explaining there were exceptions.

However, McSweeney’s lawyer, Sarah Matz of Adelman Matz, pushed back saying that “courts have never said that the limits on free speech stopped at crime.”

“You are not allowed to breach people’s rights simply because you’re pointing a camera at them,” she said during the hearing. “There is a difference between ’crafting a message’ and making a show that you think people will watch.”

The case is set to resume after Thursday, as the the defense requested that discovery — in which each side can demand to see confidential messages and files belonging to the other — in the case be put on hold until the judge has ruled on the motion to dismiss.

McSweeney appeared in court Thursday, wearing a gray power suit, black shirt and matching heels. She walked into the courthouse arm-in-arm with another woman who was wearing a large brown coat.

Cohen, meanwhile, was not present in the courthouse.

McSweeney — who starred on two seasons of “Real Housewives of New York City” — accused Cohen and Bravo in her suit, filed in February, of exploiting her alcoholism to boost ratings for the reality show.

She claimed producers, who were aware of her history of mental health and substance abuse issues, would try to destabilize her when she “refused” to drink in hopes of an on-camera meltdown.

The Married to the Mob clothing line founder, 42, also alleged that Cohen, 56, would snort cocaine with his favorite “Housewives” and dole out professional favors to his employees-turned-party pals.

She also claimed a different senior producer would send “unsolicited pictures of [their] genitalia to lower-level … production employees.”

In May, a Bravo spokesperson told Page Six that Cohen, whose rep had said McSweeney’s allegations were “false” and a “shakedown,” had been cleared of any wrongdoing following an “outside investigation.”

McSweeney’s lawyers questioned the authenticity of the probe, though, stating they didn’t think it was “real.”

Lawyer Gary Adelman said in a statement at the time, “How do you have an investigation without speaking with to anyone? As far as we know no one ever contacted our firm.”

He added, “We look forward to reviewing all of the interviews, evidence and final reports of the investigation that NBCU conducted, when we receive them during the discovery phase of the lawsuit.”

Later that month, Cohen’s lawyers filed a motion to dismiss the “RHONY” alum’s suit, arguing that the network never specifically tried to “feature inebriated cast members” on the “Housewives” franchise.

They also alleged the reality star’s claims sought to “abridge Defendants’ First Amendment rights to tailor and adjust the messages they wish to convey in their creative works, including through cast selection and other creative decisions,” per a filing previously obtained by People.

Matz, meanwhile, said in response that the defendant’s argument that they were essentially “allowed to discriminate against” their client was inaccurate.

She added, “To agree with the Defendants would be to essentially say that the creative industries are not subject to anti-discrimination and anti-retaliation laws and that networks could engage in discrimination and retaliation with impunity, which is not the law.”