Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

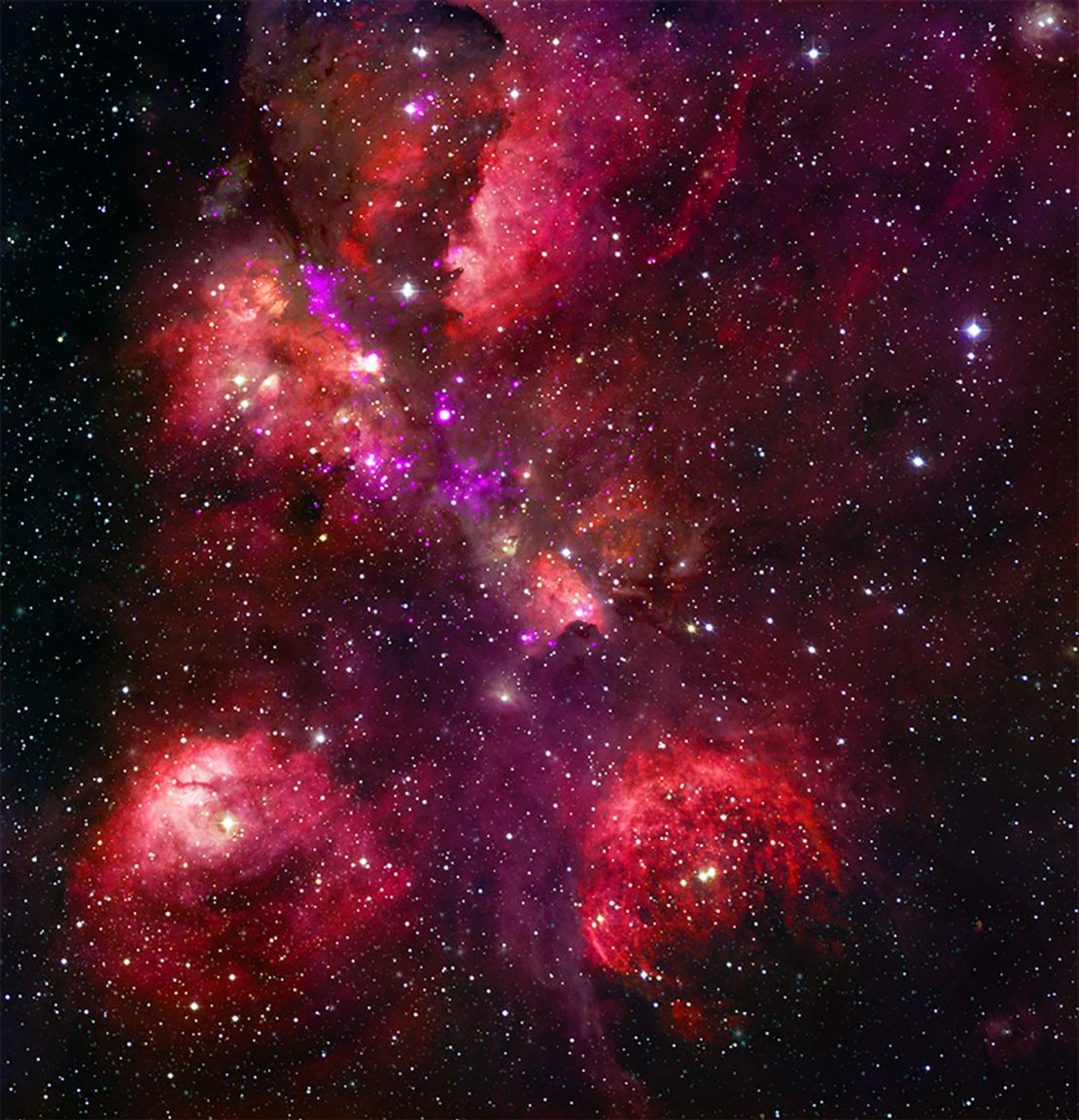

A glowing supernova remnant, a nebula shaped like a cat’s paw and the iconic “Pillars of Creation” are just a few of the celestial objects that shine in 25 never-before-seen images captured by NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory to mark the telescope’s 25th anniversary.

Chandra, named in honor of the late Indian American astrophysicist Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar, launched to space aboard the space shuttle Columbia on July 23, 1999. The crew, including STS-93 Commander Eileen Collins, deployed the telescope into its oval-shaped orbit, which takes Chandra on a path around Earth that is nearly one-third of the distance to the moon.

“On behalf of the STS-93 crew, we are tremendously proud of the Chandra X-ray Observatory and its brilliant team that built and launched this astronomical treasure,” Collins said in a statement shared Monday in a NASA release. “Chandra’s discoveries have continually astounded and impressed us over the past 25 years.”

So far, Chandra has taken nearly 25,000 observations of the universe.

The telescope observes the cosmos through X-ray light, which is invisible to the human eye. X-rays are released by some of the most energetic events and hottest objects in the universe, including exploded stars, material swirling around black holes, galactic collisions and even exoplanets.

“For a quarter century, Chandra has made discovery after amazing discovery,” said Pat Slane, director of the Chandra X-ray Center at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in a statement. “Astronomers have used Chandra to investigate mysteries that we didn’t even know about when we were building the telescope — including exoplanets and dark energy.”

But the future of the telescope could be in jeopardy due to NASA budget cuts, which threaten to prematurely conclude the mission by the end of this decade. And without another premier X-ray observatory to immediately take its place, astronomy research could suffer.

Revealing the hidden universe

The idea for the Chandra mission was first proposed in 1976 by astrophysicists Riccardo Giacconi and Harvey Tananbaum, who saw the importance of having a large X-ray telescope and initiated its design. Along with the Hubble Space Telescope and now-retired Spitzer Space Telescope and Compton Gamma Ray Observatory, Chandra is one of NASA’s “Great Observatories” launched near the turn of the 20th century that were designed to study the universe across different wavelengths of light.

The telescope has the highest-quality X-ray mirrors ever manufactured, which not only results in gorgeous imagery, but the ability to identify detailed structures that show the underlying physics of energetic cosmic objects, Slane said.

During its mission, Chandra has studied the remains of exploded stars to see how matter and energy behave in space under the most extreme conditions.

Shortly after launch, the observatory focused on what has become an iconic celestial target: supernova remnant Cassiopeia A. Chandra has returned to this feature again and again, revealing new insights each time.

The remnant is an expanding cloud of matter and energy released when a star exploded. Over time, Chandra’s X-ray data of the remnant has allowed astronomers to pinpoint a dense neutron star left by the explosion at the center of the remnant, as well as “superfluid” found inside the neutron star. The fluid suggests that the original massive star may have turned inside out as it exploded, which is helping astronomers to better understand the violent evolution of stars.

The observatory has also glimpsed the birth of stars in the Cat’s Paw Nebula and the famed “Pillars of Creation” and peered into the heart of our own Milky Way galaxy to help astronomers study the supermassive black hole at its center. And Chandra has spied massive galaxy clusters that include hundreds of thousands of glittering galaxies, as well as the superheated soup of gas around the galaxies only visible in X-ray light.

“Before Chandra, it was known that there was a sort of diffuse haze of X-ray emission coming from all directions in the sky. With Chandra, we now know that this isn’t a haze at all; it is a vast collection of distant black holes whose emissions merge together in blurrier telescopes,” Slane said.

“There are hundreds of examples like these, where Chandra’s sensitivity has brought new discoveries or provided the confirmation for existing theories,” he added. “The legacy isn’t one particular discovery, it is the unique contributions to studies of things as close as planets in our Solar System to supermassive black holes near the edge of time.”

With more than 10,000 scientific papers written based on Chandra data, the telescope is one of NASA’s most productive astrophysics missions.

An uncertain future

NASA’s budget cannot support all of its current programs while beginning new projects planned for the future, so some legacy missions such as Chandra are going to experience cuts, Slane said.

“Speaking for Chandra, the reductions would fall somewhere between dramatically reducing the scientific productivity of the observatory and the support to its community of users, or shutting the observatory down,” he said. “NASA sincerely does not want to do the latter, and the community — and Congress — have been vocal about not reducing the funding to a NASA Great Observatory that is still healthy and producing spectacular science, and with no replacement in sight. NASA is working now to consider the overall budget situation and provide final guidance for Chandra.”

Members of the astronomy community have created a grassroots campaign called Save Chandra to raise awareness and garner support for the telescope’s future.

The NASA budget allotment for Chandra will gradually dwindle in the coming years, based on the agency’s budget request released in March. While the telescope received $68.3 million in 2023, Chandra would only receive $41.1 million for operations beginning in fiscal year 2025. The budget allotment for Chandra will then drop to $26.6 million per year beginning in fiscal year 2026 and going through fiscal year 2028, and then plunge to only $5.2 million in fiscal year 2029, which would effectively end the mission.

Despite 25 years spent in space, Chandra remains in good health and virtually all of the spacecraft’s systems are in good condition, Slane said. If any issues have arisen, such as trying to keep the telescope at its cool, optimal operating temperature, the Chandra team has found creative workarounds that haven’t reduced the telescope’s efficiency, he said. And there are no concerns about the telescope running out of fuel.

While there are successor telescope concepts in mind to take Chandra’s place, such as the Lynx X-ray Observatory, with better imaging capabilities, the development of these tools has not been selected as a top priority, so there is no immediate X-ray observatory to step in should the Chandra mission conclude at the end of the decade.

Chandra plays a key role not only as an X-ray telescope, but in providing data that pairs with observations from other telescopes. Combined, all of those wavelengths of light provide a more complete picture that enables astronomers to solve the universe’s lingering mysteries. Additionally, the loss of the telescope would impact the next generation of X-ray astronomers whose research is supported by Chandra.

“The loss of Chandra, at present, would be devastating to not just X-ray astronomy, but to most of astronomy,” Slane said. “Operation into the next decade would — in addition to continuing to produce top-tier science — provide a framework in which NASA could plan for a natural continuation and growth of the US X-ray astronomprogram.”