Sixty years ago, early in the morning of October 1, 1964, a sleek blue and white train slid effortlessly across the urban sprawl of Tokyo, its elevated tracks carrying it south toward the city of Osaka and a place in the history books.

This was the dawn of Japan’s “bullet train” era, widely regarded as the defining symbol of the country’s astonishing recovery from the trauma of World War II. In tandem with the 1964 Tokyo Olympic Games, this technological marvel of the 1960s marked the country’s return to the top table of the international community.

In the six decades since that first train, the word Shinkansen – meaning “new trunk line” – has become an internationally recognized byword for speed, travel efficiency and modernity.

Japan remains a world leader in rail technology. Mighty conglomerates such as Hitachi and Toshiba export billions of dollars worth of trains and equipment all over the world every year.

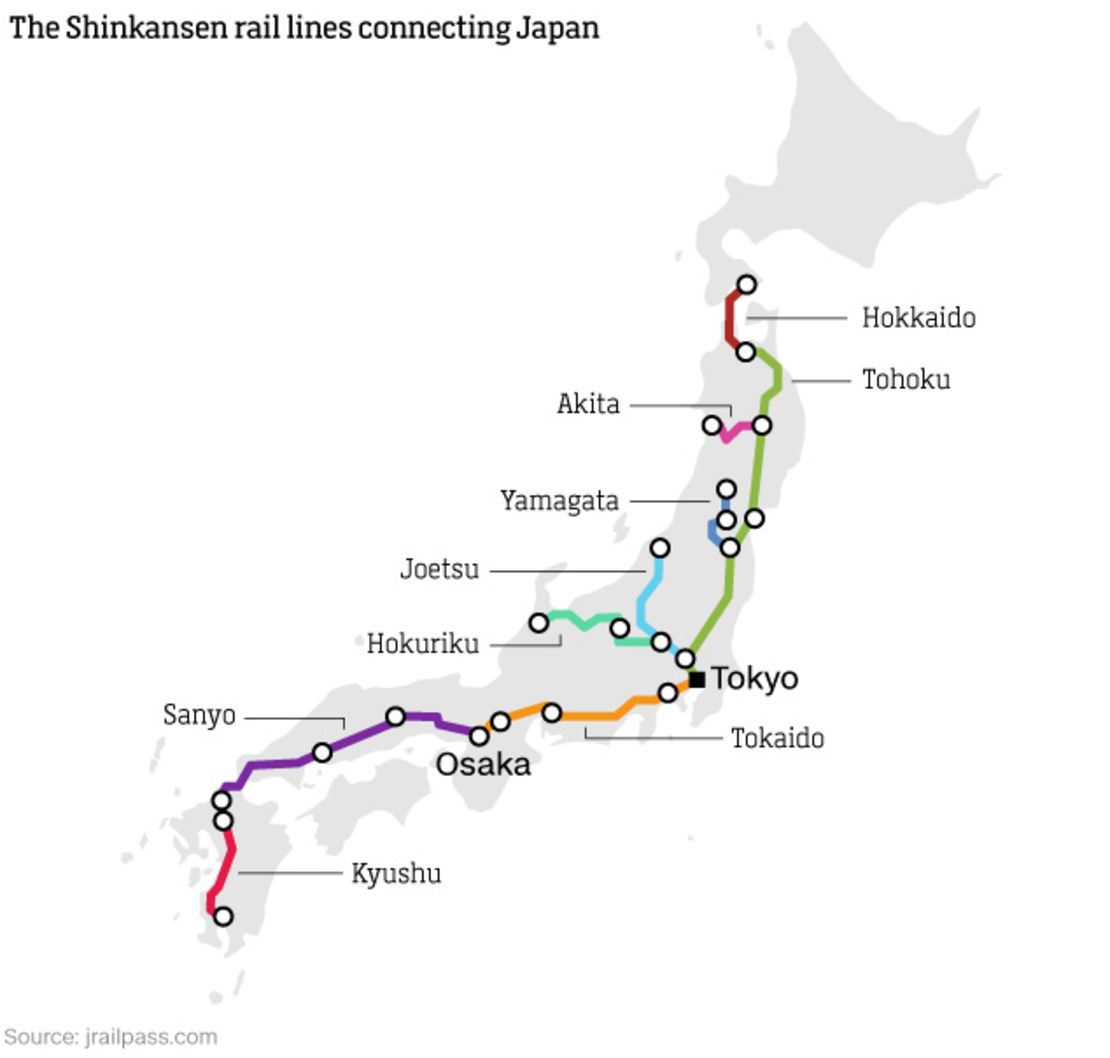

The Shinkansen network has expanded steadily since the 320-mile Tokaido line, linking Tokyo and Shin-Osaka was completed in 1964. Trains run at up to 200 mph (about 322 kph) on routes radiating out from the capital – heading north, south and west to cities such as Kobe, Kyoto, Hiroshima and Nagano.

As well as a symbol of recovery, Shinkansen have been used as a tool for Japan’s continuing economic development and an agent of change in a country bound by convention and tradition.

Pushing the boundaries

Its development owes a great deal to Japan’s early railway history. Rather than the 4ft 8.5in “standard” gauge used in North America and much of Europe, a narrower gauge of 3ft 6in was chosen.

Although this was cheaper and easier to build through mountainous terrain, capacity was limited and speeds were low.

With Japan’s four main islands stretching around 1,800 miles (nearly 3,000 kilometers) from end to end, journeys between the main cities were long and often tortuous.

In 1889, the journey time from Tokyo to Osaka was 16 and a half hours by train – better than the two to three weeks it had taken on foot only a few years earlier. By 1965, it was just three hours and 10 minutes via the Shinkansen.

Demands for a “standard gauge” rail network started in the 20th century, but it was not until the 1940s that work started in earnest as part of an ambitious Asian “loop line” project to connect Japan to Korea and Russia via tunnels under the Pacific Ocean.

Defeat in World War II meant that plans for the new railroad were shelved until the mid-1950s, when the Japanese economy was recovering strongly and better communications between its main cities was becoming essential.

Although much of the network serves the most populous regions of Honshu, the largest of Japan’s islands, lengthy sea tunnels allow bullet trains to run hundreds of miles through to Kyushu in the far south and Hokkaido in the north.

Japan’s challenging topography and its widely varying climates, from the freezing winters of the north to the tropical humidity farther south, have made Japanese railroad engineers world leaders at finding solutions to new problems as they push the boundaries of rail technology.

Not least of these is seismic activity. Japan is one of the most geologically unstable places on the planet, prone to earthquakes and tsunamis and home to around 10% of the world’s volcanoes.

While this provides arguably the defining image of the Shinkansen – a high-tech modern train flashing past the snow-capped Mount Fuji – it also makes the safe operation of high-speed trains much more difficult.

Despite these factors, not a single passenger has ever been killed or injured on the Shinkansen network due to derailments over its history.

Japan’s high-speed rail revolution

Japan’s high-speed rail revolution

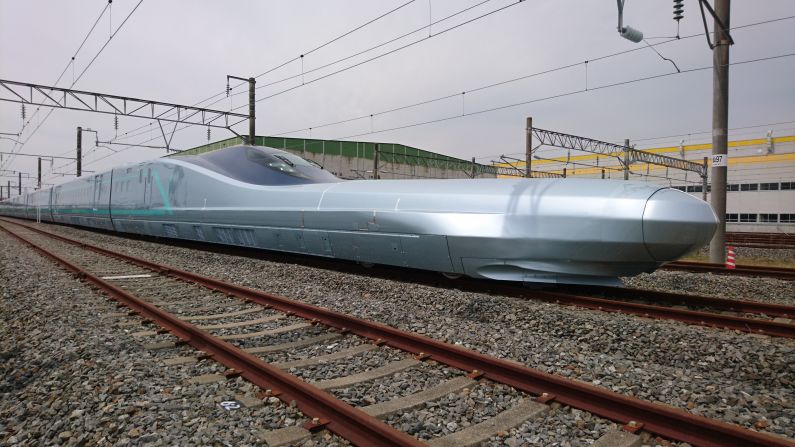

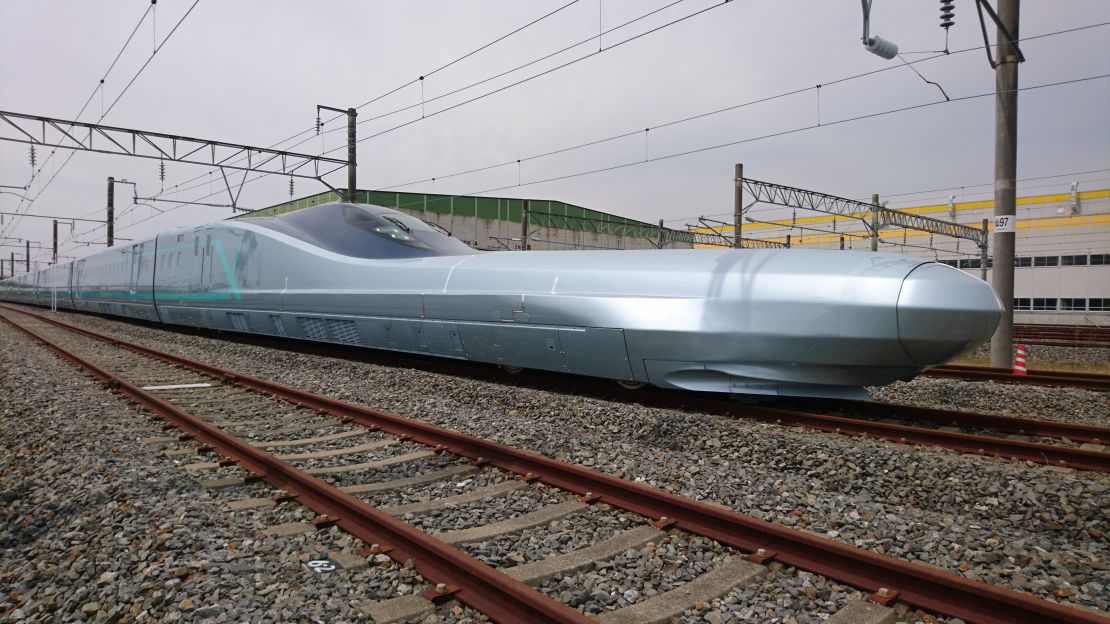

The next generation of bullet trains, known as ALFA-X, is currently being tested at speeds of almost 250 mph (400 kph), although the service maximum will be “only” 225 mph.

The defining features of these and other recent Shinkansen trains are their extraordinarily long noses, designed not to improve their aerodynamics, but primarily to eliminate sonic booms caused by the “piston effect” of trains entering tunnels and forcing compression waves out of the other end at supersonic speeds.

This is a particular problem in densely populated urban areas, where noise from Shinkansen lines has long been a source of complaints.

The experimental ALFA-X train also features new safety technology designed to cut down on vibration and noise and reduce the likelihood of derailments in major earthquakes.

More than 10 billion passengers have now been carried in speed and comfort by the trains, the predictability of the operation making high-speed travel seem routine and largely taken for granted.

High-speed rails around the world

In 2022, more than 295 million people rode on Shinkansen trains around Japan.

Little wonder then that many other countries have followed Japan’s example and built new high-speed railroads over the last four decades.

Perhaps the best-known of these is France, which has been operating its Train à Grand Vitesse (TGV) between Paris and Lyon since 1981.

Like Japan, France has successfully exported the technology to other countries, including Europe’s longest high-speed network in Spain, as well as Belgium, South Korea, the United Kingdom and Africa’s first high-speed railroad in Morocco.

France’s TGV network has been phenomenally successful, slashing journey times over long distances between the country’s big cities, creating additional capacity and making high-speed travel accessible and affordable, even mundane for regular commuters.

Italy, Germany, the Netherlands, Taiwan, Turkey and Saudi Arabia all now operate trains on dedicated lines linking their major cities, competing directly with airlines on domestic and international routes.

In the UK, high-speed Eurostar trains run from London to Paris, Brussels and Amsterdam, but “High Speed 2,” a second route running north from London has been mired in controversy. What was once billed as a landmark mega-project to power an interconnected Britain into the oncoming century has now been reduced to a 140-mile link that will barely improve on existing services.

For the moment, the closest equivalent to the bullet train for British passengers are new Hitachi-built “Intercity Express Trains” using technology derived from their Japanese cousins, although these only run at a maximum of 125 mph.

Meanwhile, India and Thailand are planning extensive high-speed rail networks of their own.

China’s railway rise

In recent years, it’s China that has eclipsed the rest of the world, using its economic might to create the world’s longest high-speed railroad network.

According to the country’s national railway operator, the total length stands close to 28,000 miles as of the end of 2023.

More than just a mode of transportation, these lines provide fast links across this vast country, stimulating economic development and cementing political and social harmonization.

Using technology initially harvested from Japan and Western Europe, and subsequently developed by its increasingly sophisticated railroad industry, China has quickly made itself a leading player in high-speed rail.

This looks set to continue as it develops magnetically levitating (Maglev) trains capable of running at almost 400 mph.

Japan has had its own experimental Maglev line since the 1970s and is constructing a 178-mile line between Tokyo and Nagoya.

Due to open in 2034, it will eventually extend to Osaka, cutting the journey time to the latter to just 67 minutes.

“The Shinkansen is clearly much more than a means of transportation,” says British academic Christopher P. Hood, author of “Shinkansen: From Bullet Train to Symbol of Modern Japan.”

“It was the most potent symbol of Japan’s postwar reconstruction and emerging industrial might and as it continues to evolve is likely to be so for many years to come.”

Although the iconic blue and white 0-Series trains of 1964 are long since retired, they still form many people’s image of what a bullet train looks like.

Their remarkable descendants are an indispensable part of the transport infrastructure in Japan and many other countries around the world and, as environmental concerns make people think twice about flying, they could be about to experience a further resurgence, prompting a new golden age for the railroad.