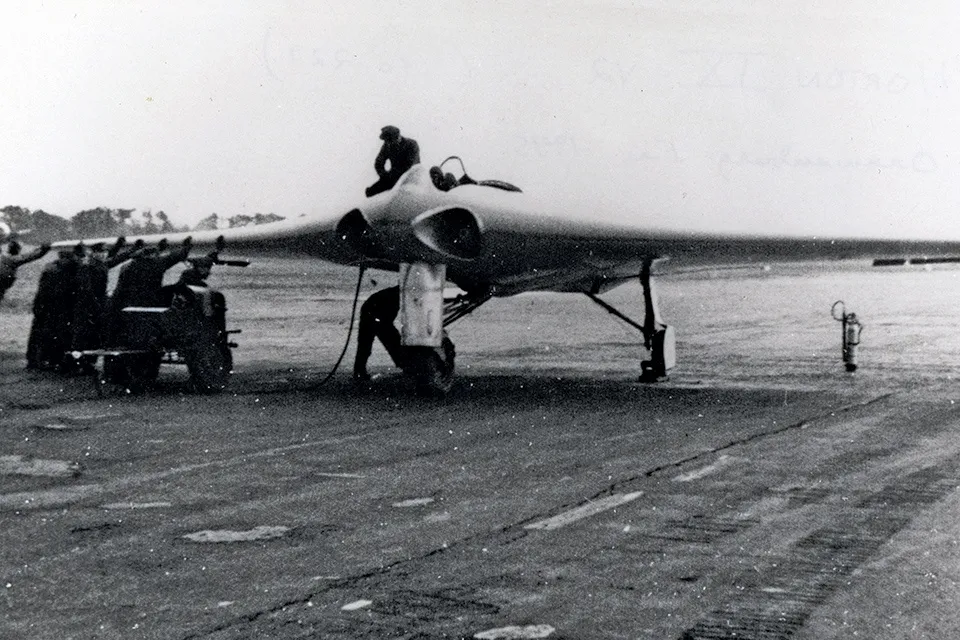

The Hortens weren’t Burt Rutans. Talented, yes, but not the aeronautical geniuses they’ve been called by some. They built a series of increasingly sophisticated iterations of the same basic design—graceful sweptwing, tailless gliders, though several of their wings were powered. The Hortens produced a grand total of 44 airframes of their dozen basic designs. History has portrayed them as aeronautical visionaries, for in 1940 Messerschmitt Me-109 pilot Walter Horten, who scored seven Battle of Britain victories as Adolf Galland’s wingman, proposed putting a pair of Germany’s new axial-flow jet engines into a Horten glider. The result was the Ho IX. (Brother Reimar was the aerodynamicist and designer; Walter was the facilitator, eventually holding an important Luftwaffe position that allowed him to divert government supplies, staff and facilities for his brother.)

The jets were first going to be two BMW 003s, but when they underperformed the Hortens switched to Junkers Jumo 004Bs. The Ho IX V2 (Versuch 2, or Test 2—the V1 was an unpowered research glider) officially flew three times, crashing fatally at the end of the third flight when one of its two Jumos failed.

No Horten IX ever flew again, but the brothers had undeniably built and tested the world’s first turbojet flying wing. The Ho IX V2 first flew in March 1945, more than three and a half years before Northrop’s eight-jet YB-49 flying-wing bomber took off. In a number of ways, the Hortens were well ahead of Jack Northrop and his engineers, though Northrop never admitted that. After the war, it was suggested to Northrop that he hire the brothers. “Forget it, they’re just glider designers,” he said condescendingly. The success of the Ho IX was pointed out to him, but Northrop dismissed it as a Gotha design, not a Horten.

No Horten IX ever flew again, but the brothers had undeniably built and tested the world’s first turbojet flying wing. The Ho IX V2 first flew in March 1945, more than three and a half years before Northrop’s eight-jet YB-49 flying-wing bomber took off. In a number of ways, the Hortens were well ahead of Jack Northrop and his engineers, though Northrop never admitted that. After the war, it was suggested to Northrop that he hire the brothers. “Forget it, they’re just glider designers,” he said condescendingly. The success of the Ho IX was pointed out to him, but Northrop dismissed it as a Gotha design, not a Horten.

Northrop was wrong, but the source of his confusion was the fact that the Luftwaffe, knowing the tiny Horten garage operation could never mass-produce twin-engine jet fighter-bombers, turned the project over to Gotha, a large railroad car manufacturing company with aircraft-building experience. As a result, the Horten jet has come down to us with a confusing suite of names. The actual sole jet-powered wing that flew was the Ho IX V2. The German air ministry (Reichsluftfahrtministerium, or RLM) gave the project an official make and model designation—Ho-229. Because production was assigned to Gotha, some sources still refer to the airplane as a Go-229. Many Luftwaffe aircraft were built by a variety of manufacturers, but a Junkers remained a Ju, a Heinkel an He, a Dornier a Do no matter who actually manufactured it, so “Go-229” is a misnomer. The Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, citing the RLM designation, calls a major artifact in its collection that is about to undergo serious conservation a Horten 229. This despite the fact that no production Horten 229 ever existed; what the Smithsonian has is the never-completed Ho IX V3 built by Gotha.

It bears mentioning that neither Northrop nor the Hortens invented flying wings. Both the concept and actual flying wings have been around since the 1910s. In fact, by the late 1920s, there had been enough experiments with flying wings that the configuration was considered passé, and both Jack Northrop and the Hortens were late to the party.

The Hortens have also been credited with designing and building the world’s first stealth fighter. That is a more difficult claim to support. It’s a popular fiction in the “Hitler’s wonder weapons” community, and it got a boost in a 2009 Northrop Grumman–sponsored film, Hitler’s Stealth Fighter, a National Geographic documentary. The doc tried to show that a modern replica of the National Air and Space Museum’s Ho IX V3 bombarded by microwaves revealed moderate radar-deflecting properties. Northrop Grumman’s prototyping shop built the replica for $250,000. That’s a bargain for an hour-long video broadcast on the History Channel that is still being discussed by what some call the “Napkinwaffe”—a dig at where the plans for some of the Luftwaffe’s fantasy fighters were first sketched. (Engineering drawings for the Horten jet reveal this to be not far from the truth.)

Northrop Grumman built the Horten replica entirely of wood, its plywood skins layered with radar-absorbent carbon-impregnated glue. Only the externally radar-visible instrument panel backing and first-stage compressor disks were metal. Yet the Horten brothers’ original airplane also had an 11-foot-wide center section made of welded steel tubing, and it carried two turbojet engines. Neither of these were part of the Northrop Grumman replica. It could be argued that all this metal might have reflected at least some microwave energy that penetrated the plywood. But Northrop Grumman felt that their special glue made the replica totally opaque to radar.

The replicators also left out the original Ho IX V3’s eight large aluminum fuel tanks. Nor did Northrop Grumman include the underwing bombs that would have been necessary for any attack on a radar-defended target. Externally racked ordnance destroys any semblance of stealth. The Nat Geo film ended up suggesting that an all-wood Horten might have been able to do a fly-by of Britain’s by then obsolete Chain Home low-frequency radar array, but it wouldn’t have been able to bomb anything.

Narration over the film says that it reveals “just how close Nazi engineers were to unleashing a jet that some say could have changed the course of the war.” Not bloody likely, if only because by that time, the Germans were literally out of gas.

The heart of the Horten stealth assertion is a claim by the brothers, made long after the war ended, that they indeed had intended to fasten the layers of the Ho-229’s plywood sheathing with glue mixed with radar-absorbing charcoal. Perhaps they did mean to do that, but the first mention of this plan came in a 1983 book written by Reimar, at a time when the basics of U.S. stealth technology were becoming public knowledge. There is no mention of any attempt to achieve stealthy properties for the Ho-229 by anybody involved in the actual fabrication of the prototypes.